On September 30, the Dutch government invoked its rarely used Goods Availability Act to take control of Nexperia, a semiconductor company owned by China’s Wingtech Technology. Officials cited acute governance concerns and risks to Europe’s technological security.

What is Nexperia?

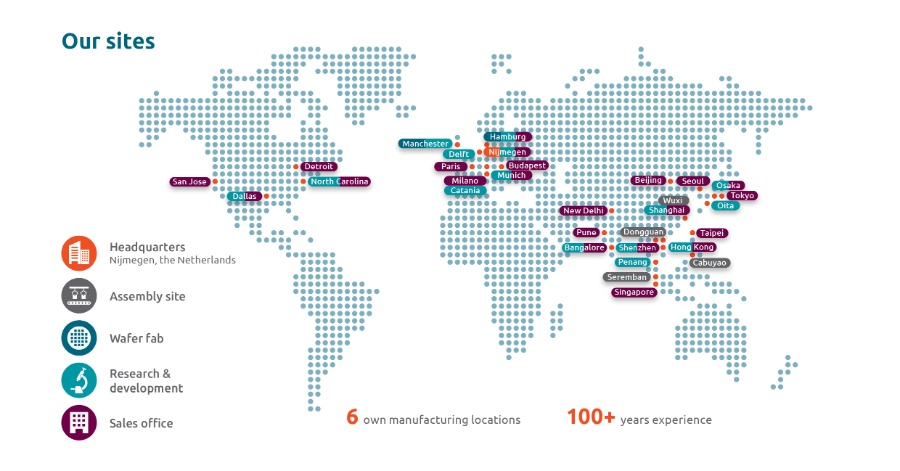

Nexperia is a leading Dutch semiconductor manufacturer based in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, producing essential chips for global technology industries.

The company traces its origins to the early 20th-century innovations of Philips, which acquired the British firm Mullard and Germany’s Valvo in the 1920s to build a European microelectronics powerhouse. In 2006, NXP Semiconductors purchased a 80.1% stake of the semiconductor division from Philips. This newly formed consortium included private equity firms such as KKR, Bain Capital, and Silver Lake Partners. In 2015, JAC Capital agreed to purchase NXP for $1.8 billion. Wingtech then acquired Nexperia from this Beijing-based asset management firm for $3.8 billion, in 2018.

With 30% ownership by Chinese national and regional governments, Nexperia employs 12,500 people in Europe, Asia and the US. Its largest manufacturing site is in Hamburg, Germany. Nevertheless, most of its chips are packaged and assembled into larger products in China.

According to Reuters, Nexperia does not make advanced processors or AI chips. Instead, it is specialised in “discrete components” such as diodes and transistors. These chips may not drive AI revolutions, but they are crucial in the automobile, telecom and defence industries.

What did the Dutch government do?

Vincent Karremans, the Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs, announced the intervention under the Goods Availability Act (Wet beschikbaarheid goederen). This Cold War-era law created in 1952 allows the government to block key decisions about hiring staff or relocating company parts for one year.

On a letter to the Parliament, this cabinet member justified the use of this legal instrument on the basis of “serious indications of governance shortcomings within Nexperia, arising from specific actions by the CEO.”

The Minister highlights a “threat to the continuity of the company and thus the preservation of critical technological knowledge.” According to Karremans, the shortcomings are related to “the improper transfer of production capacity, financial resources, and intellectual property rights to a foreign entity owned by the CEO and not connected to Nexperia.”

In its statement, the government claims that the intervention would protect economic security in Netherlands and in Europe.

What has led up to this?

A climate of escalating technology tensions shaped the intervention. On September 29, one day before the Dutch order, the United States expanded its export controls. The Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) extended the restriction to entities at least 50% owned by one or more blacklisted Chinese firms.

Although Nexperia was not directly listed, it was affected through its parent company, Wingtech Technology, blacklisted last December. Washington accused Wingtech of aiding Beijing in acquiring and relocating foreign semiconductor firms with technologies critical to Western defense industries. In its official notice, BIS stated that such actions “contradict the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States.”

On October 1, Amsterdam’s commercial court decided to suspend Wingtech CEO Zhang Xuezheng from his position. The chamber found this executive guilty of a conflict of interest via his controlling stake in a Shanghai-based firm WSS. Such company manufactures wafers, the key components in semiconductors.

According to the Court, the CEO forced Nexperia to order as much as $200 million of wafers from WSS in 2025, when it only needed around $70-80 million. The ruling highlights that the surplus of wafers would just “be held in stock until obsolete.”

Three days later, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced new export controls on rare-earth metals and certain semiconductor sub-assemblies.

What effects of this operation have already been seen?

The immediate reaction in China was of anger. The tabloid Global Times, ran by the Communist Party, accused Amsterdam of taking “predatory actions” that constituted a “serious harassment” of Wingtech.

According to this editorial, the takeover operation is “a blatant trampling of international rules by the Netherlands.”

The European Union expressed support for the Dutch action. Commission spokesman Olof Gill signalled the importance of protecting technological security as a priority in the EU Security Strategy.

Automotive and consumer-electronics manufacturers are now monitoring the situation closely. Nexperia’s large-scale production of chips for vehicles and other goods means that any extended supply disruption would ripple through global value chains.

The Dutch government has emphasised that Nexperia’s day-to-day production will continue. Meanwhile, decisions such as asset transfers, executive appointments or major strategic moves may now require prior approval under the invoked legal framework.

Market and management effects

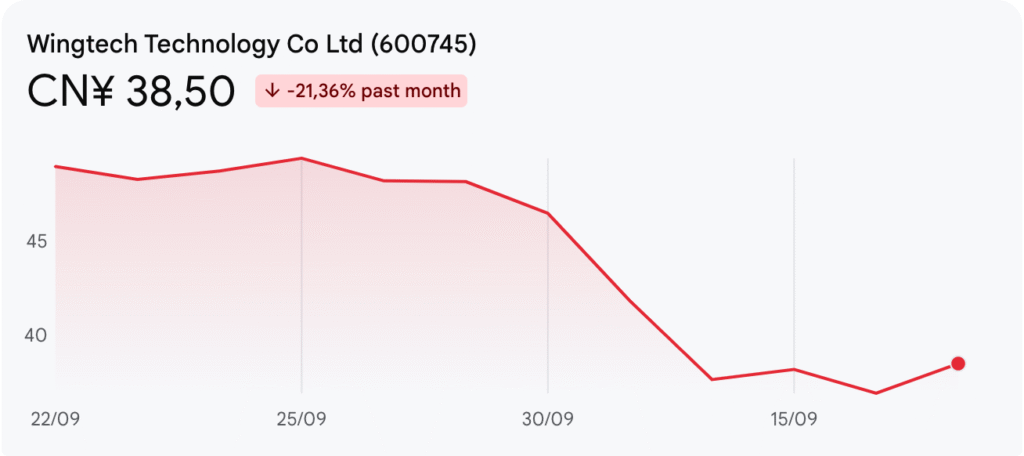

Following the Dutch announcement, Wingtech’s shares on the Shanghai Stock Exchange fell by over 8 percent within two trading days, erasing roughly US$ 1.2 billion in market capitalisation. The decline reflected both investor uncertainty and expectations of tighter European scrutiny of Chinese acquisitions.

Former CFO Stefan Tilger substituted CEO Zhang Xuezheng after the Dutch takeover. Nevertheless, Nexperia China told employees to follow the instructions of the domestic management team.

The authorities target such statements not only at in-person communication, but also at Outlook and Teams. This may signal a potential split of the Chinese branch.

Outlook

For now, Nexperia continues operations under government supervision. Vincent Karremans, the Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs, has opened talks with Chinese officials to discuss the matter. The two sides need to work in order to prevent a supply chain crisis that could hit the global automobile industry, from Volkswagen to BYD.

Following on the line of thought we made on the Automotive Trade War article, the Netherlands will have to balance economic nationalism with the realities of a globalised supply chain.

Author: Luigi Lombardo

N.B. This case is meant for discussion only. It has been prepared for courses in Global Strategy, International Business, Geopolitics and Political Sciences.