The return of power politics

In a recent article for Il Sole 24 Ore, Professor Andrea Colli argues that the decline of multilateralism is not necessarily irreversible. He recalls that cooperation among states, based on shared rules and institutions, has always depended on leadership. A hegemon — capable of enforcing norms and guaranteeing stability — makes collaboration possible. When that leadership fades, institutions lose strength, and rivalries return.

Multilateralism is about cooperation. It works through institutions of global governance, and assumes that countries see mutual benefit in acting together.

Multipolarity, by contrast, is about competition. It describes a world where several powers all seek influence. No single actor dominates, and each defends its interests more assertively.

The shift towards multipolarity explains the return of power politics. This term, popularised by the German sociologist Friedrich Meinecke, reflects the idea of foreign policy driven primarily by national interest, power, and survival. Nowadays, States have been “waging wars” on new territories of power. These involve technologies, such as those for the green transition; and artificial intelligence.

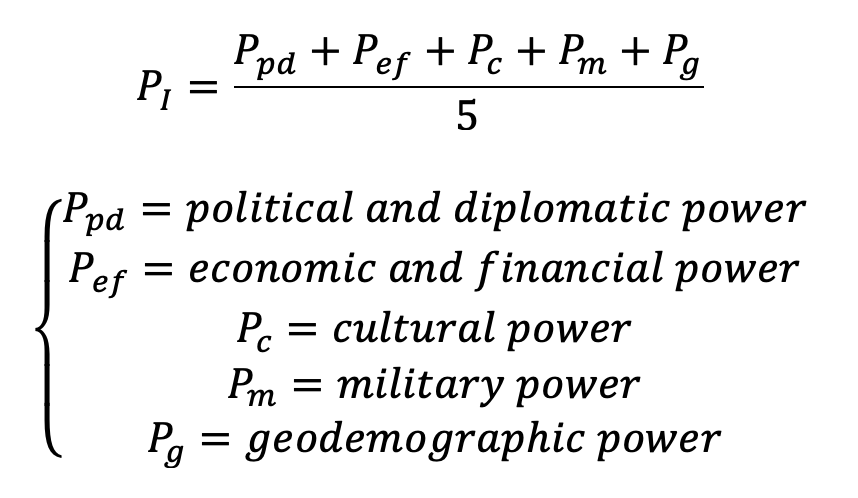

One interesting quantitative lens to understand power politics is Professor Castro’s International Power Index (PI). His measure illustrates how states’ power is not only exercised militarily, but also culturally or demographically. We outline his method more in detail in this separate article. Colli’s historical reflection and Castro’s quantitative framework together reveal the same reality: power is diversifying, not disappearing.

Colli’s warning is timely. As multipolarity replaces the U.S.-led order that followed the Cold War, the cooperative spirit of multilateralism faces growing pressure. Yet new forms of leadership — shared, regional, and issue-based – may still allow the system to adapt rather than collapse.

Cooperation as a force for multilateralism

Colli recalls how modern multilateralism emerged from the ashes of World War II, underpinned by American leadership and the Bretton Woods institutions – the IMF, World Bank, and later the GATT/WTO.

These were not altruistic projects, but pragmatic arrangements that aligned U.S. national interest with global recovery. US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau captures this relationship clearly at the close of the Bretton Woods Conference:

“We have come to recognise that the wisest and most effective way to protect our national interests is through international co-operation.“

Nowadays, the same system has been facing strain from within. The World Trade Organization has been weakened by nationalist policies and persistent trade disputes. The UN Security Council is paralysed by veto politics. Meanwhile, new coalitions such as the BRICS group are seeking to expand and redefine global cooperation outside traditional Western frameworks.

Now including countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Argentina; the BRICS bloc challenges the Bretton Woods order by calling for fairer representation and new financial mechanisms. Yet, some analysts highlight power asymmetries within the members of the group themselves. This features a key tension: multipolarity promises inclusiveness but risks incoherence.

The fragile logic of multipolarity

As Colli notes, multipolarity historically breeds instability. When several powers compete for dominance without a shared framework, cooperation becomes transactional and short-lived. The 19th-century Concert of Europe and the interwar League of Nations both collapsed when rising powers challenged existing hierarchies.

The lesson is clear: without a hegemon or a cohesive coalition enforcing rules, institutions decay and crises escalate. The ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, and growing tensions in the South China Sea, echo this structural fragility. Power is diffusing faster than governance can adapt.

A different kind of leadership?

Yet, unlike the 1930s, the world today is far more economically interdependent. Supply chains, technology, and climate challenges force even rivals to cooperate. Middle powers – from India and Brazil to the EU – may not dominate, but they increasingly shape the agenda in trade, sustainability, and regional security.

Colli’s call to recognise the role of “a willing and accepted hegemon” invites a deeper question: can leadership in the 21st century be shared rather than singular?

The emergence of plurilateral agreements — such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or EU Green Deal — suggests a form of functional multilateralism, where coalitions of the willing act without universal consensus.

Colli’s warning is timely. As multipolarity replaces the U.S.-led order that followed the Cold War, the cooperative spirit of multilateralism faces growing pressure. Yet, history also shows that multilateralism has revived before – often after periods of crisis.

Power and cooperation are not opposites. They are complementary forces that can either reinforce or destroy one another. The real challenge is not to choose between them, but to design institutions capable of balancing both. Whether the next phase of global order will be defined by shared leadership or renewed confrontation remains an open question.

We also recommend you to read…

Technology, Geopolitics, and Business: Professor Andrea Colli’s Insights

THE GLOBAL AI SUMMIT ON AFRICA: a continental strategy for artificial intelligence